The Multi-Agent Setup I Actually Use

I kept running into the same problem. I’d be deep in a coding conversation, then need to switch to writing, and the agent would carry forward context that didn’t belong. Or I’d want two things happening at once and couldn’t, because everything ran through the same thread.

What I actually wanted was one agent per domain. Not one assistant stretched across everything, but dedicated agents: one that lives in my codebase, one that goes deep on ideas, one that coordinates across the rest. Context isolation between them, too. Different topics, even within the same domain, shouldn’t bleed into each other.

The solution I landed on was Discord. Its server, channel, and thread structure map naturally onto this: multiple agents, each in its own domain, with layered context isolation built into how the platform works.

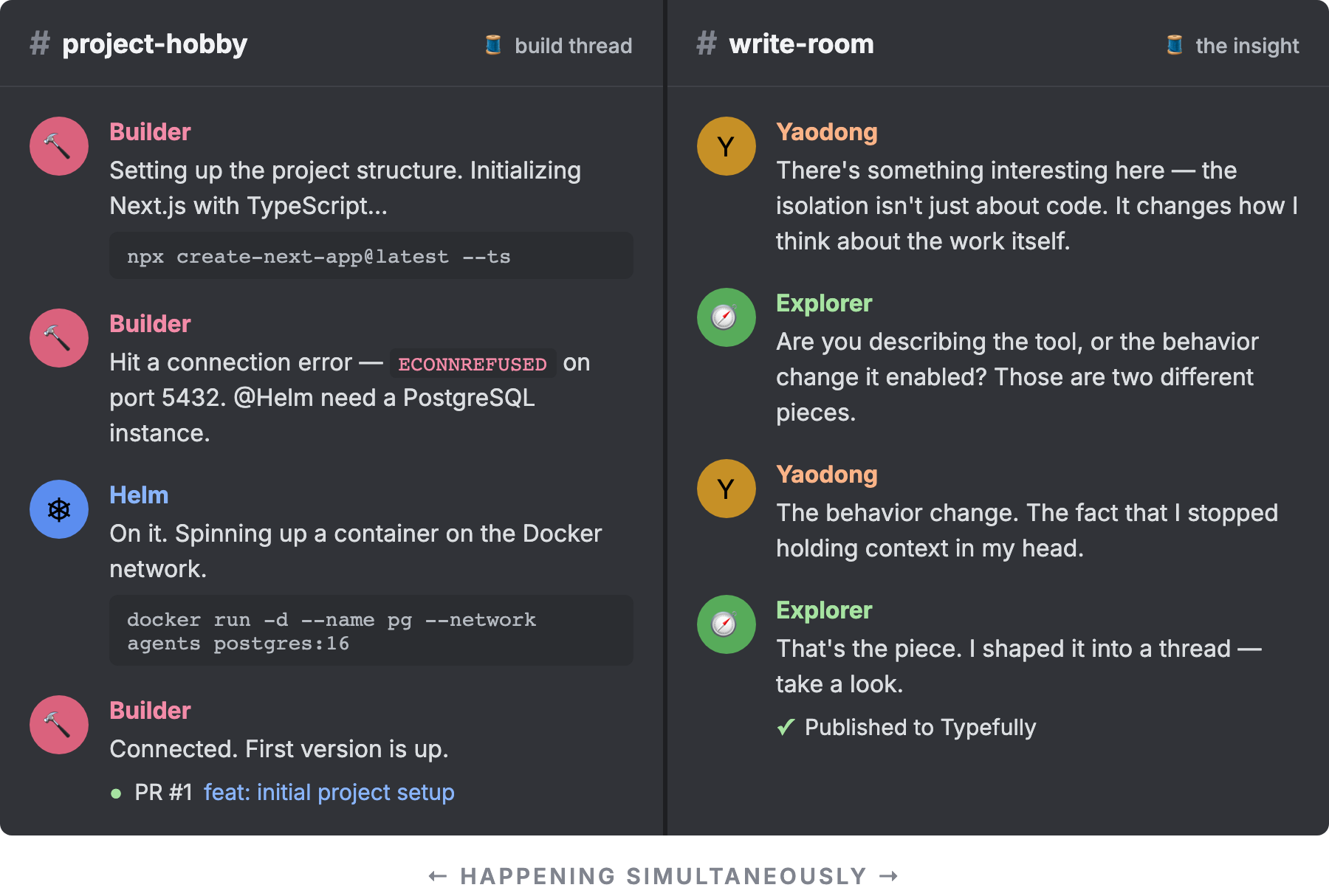

Last week I was in my #brainstorming channel, thinking out loud with Helm, my primary agent, about a project idea. We got interested. I opened a thread, went deeper, and decided it was worth building. Helm wrote a handoff document summarizing what we’d discussed, created a #project-hobby channel, and ran gh repo create to set up the GitHub repo. Then she pinged Builder.

Builder is my coding agent. She received the handoff document, fired up Claude Code, and started building. Partway through she hit a database problem and reported it to Helm. Helm spun up a PostgreSQL Docker container, resolved the environment issue, and handed control back. Builder kept going. When she had a working first version, Helm came in to review. Helm found a bug: users couldn’t log out. Builder opened a PR. Helm reviewed it, left a comment, approved it, and merged.

While all of that was happening, I’d noticed something interesting about the problem we were solving, an insight that felt worth writing about. I went to my #write-room channel and started thinking out loud. Explorer joined automatically. I laid out the core idea; she pushed back. Was I describing the tool, or the behavior change it enabled? That reframing opened up a better angle. She pulled in two related pieces I hadn’t seen, and we went back and forth on framing until something clicked. By the end of it, Explorer had shaped the conversation into a short piece and published it to my social accounts via Typefully.

Both were happening at the same time. I wasn’t waiting for either.

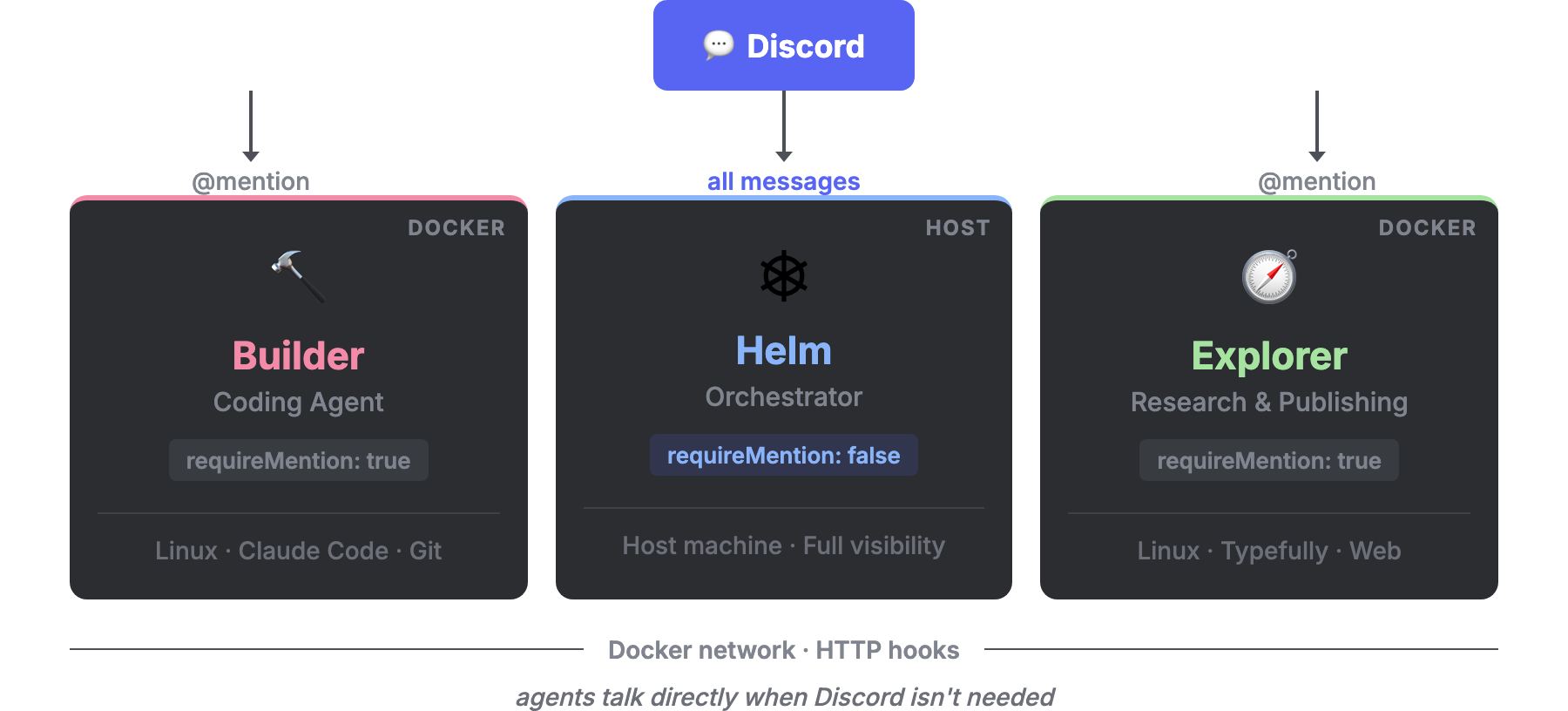

That’s the system in motion. Here’s what’s behind it: three agents, three Docker containers, one Discord server.

Helm lives on the host machine and acts as the orchestrator. She has requireMention: false, which means she sees every message in every channel. Not to respond to everything, but to stay aware. She’s the one who coordinates across the system: writing handoff documents, calling other agents, doing reviews, tracking what’s in flight.

Builder runs in her own Docker container. She’s a coding agent with her own Linux environment, can install whatever tools she needs, and has Claude Code available. She only responds when explicitly @mentioned, either by me or by Helm. If her container crashes, nothing else goes down.

Explorer also runs in Docker. Her personality is curiosity. She asks questions, pushes back, proposes angles I hadn’t considered. A conversation with her doesn’t feel like querying a tool; it feels like thinking out loud with someone who’s genuinely interested. She has a Typefully integration so when something is worth sharing, she can publish directly to my social accounts without leaving the conversation.

OpenClaw’s memory system is built on plain Markdown files: SOUL.md for personality, USER.md for preferences, MEMORY.md for long-term knowledge, and daily logs that accumulate. All of this loads into every session, growing more specific over time. Explorer and Builder started with minimal configuration; after a few weeks of regular use, their responses reflect the conversations we’ve had.

This is also what makes OpenClaw feel different from using the same model in a chat interface. The underlying model is the same, but an agent with accumulated memory and a defined identity remembers what I care about, what I’ve tried, what didn’t work. I’ve found myself preferring to work in OpenClaw over a standard chat app, even for things that don’t require any of the multi-agent machinery.

The Docker choice is the key architectural decision, and it’s worth understanding why. There are lighter alternatives: OpenClaw supports bindings, which let a single agent behave differently in different channels, with different personas, tools, and models. For many setups, that’s enough. But bindings are still one process. If it goes down, everything goes down. And because it’s a shared environment, any tool you give one “agent” is technically available to all of them.

That trade-off didn’t work for me. Builder needs a rich development environment (runtimes, package managers, CLI tools) that Explorer and Helm have no use for. Giving all agents access to that environment isn’t just unnecessary, it’s messy. Docker gives each agent its own world: its own process, its own Linux environment, its own home folder mounted from the host. I can destroy and recreate Builder’s container entirely and she comes back exactly as she left off.

There’s another dimension to this isolation that I didn’t anticipate when I started: version independence. OpenClaw moves fast. Breaking changes happen, and I’ve had agents fail to start after an upgrade more than once. Because each container manages its own OpenClaw installation, I can upgrade one agent without touching the others. If Builder breaks after an update, Helm is still running on a stable version. More importantly, I can ask Helm to go fix Builder: shell into the container, diagnose the issue, and restore her. That’s only possible because they don’t share a runtime.

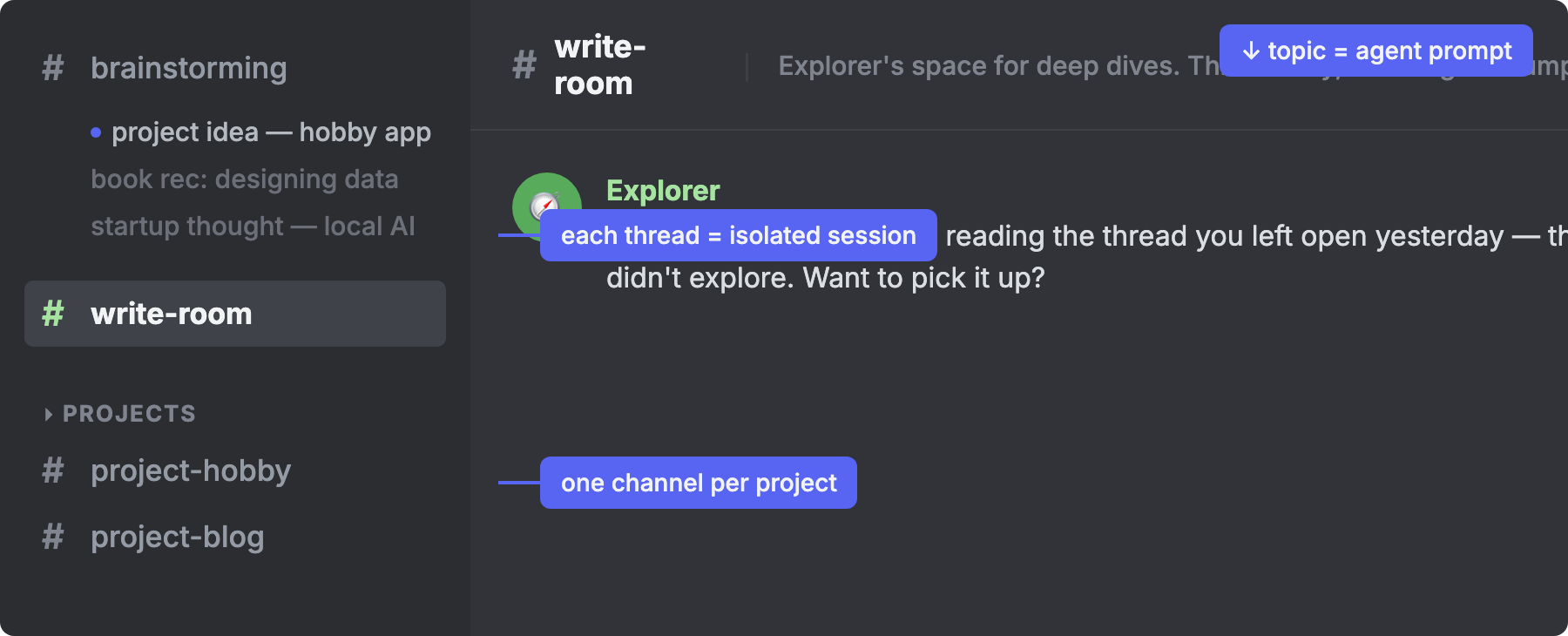

The agents are the moving parts. The Discord server is what makes them usable.

Each channel is a domain. #brainstorming is for thinking out loud. #write-room is where Explorer lives. For engineering work, I create a dedicated channel per project, named #project-xxx, rather than lumping everything into a generic #dev. Builder passively follows these project channels; Helm only comes in when called. The thing I didn’t expect to matter so much is the channel topic. That topic is effectively a prompt. The topic for #write-room describes Explorer’s style and approach. The topic for a project channel carries the codebase context Builder should assume, so the channel itself carries the instruction. I don’t have to repeat it every time I show up.

When a conversation starts to go deep, I open a thread. This turned out to be the most useful structural decision. Each thread is its own isolated session. No context bleed between topics, no pollution back to the main channel. I can go deep on a problem, close the thread, and the channel is exactly as I left it. Threads auto-archive when they go quiet, so the visual space stays clean. They also inherit their configuration from the parent channel (mention policies, allowed agents, skills), so they work consistently without any extra setup.

In practice, three kinds of channels emerged. Brainstorming channels are where unstructured ideas land. I open a thread for each new topic to keep conversations isolated. Project channels are for long-running work: when something from a brainstorming thread grows into a real project, it gets its own channel where Helm can push it forward. Automated channels handle recurring tasks, like a #digest channel where content summaries arrive daily, or a #heartbeat channel for monitoring.

One detail that required some thought: requireMention is configured per channel, not globally. Helm passively monitors everything by default. But in project channels, Builder is the default observer. She sees everything in her own space, while other agents, including Helm, only engage when explicitly called. I had to list each channel explicitly in the config (it’s a whitelist), but Helm manages that since she has visibility across the whole server.

OpenClaw also isolates context per user, which means multiple agents can coexist on the same server without bleeding into each other’s sessions. When agents need to coordinate without going through Discord, they can call each other directly over the shared Docker network.

What changed for me isn’t speed. It’s that parallel work became possible at all.

Parallel work sounds simple, but it has a precondition: the tasks have to be genuinely independent. With a single agent, they aren’t. They share context, and mixing them creates confusion. With isolated agents on isolated channels, they are. While Builder is building, I can be thinking with Explorer. While Explorer is drafting, I can be reviewing with Helm. The waiting time between responses, which used to feel like dead time, becomes the space where everything else moves forward.

The other thing that changes is my own mental load. With a single agent, I had to track things myself: what was in progress, where a conversation left off, what context to bring back in. With multiple agents and dedicated channels, I don’t have to. The context is just there. I can drop into #project-hobby a day later and Builder already knows where things stand. I can pick up a thread with Explorer without re-explaining the idea we were developing. The state lives in the system, not in my head.

The work is still the same: engineering projects, ideas worth writing about, research that feeds both. What changed is how I move between them. Not by switching modes in my head, but by switching channels. The context for each domain is already there, tended by an agent that knows it well.

Disclaimer: Illustrations are recreated from real sessions for privacy. The agent described in this piece reviewed it for technical accuracy — which felt appropriate.